In this video blog post, Jonathan Trump from the Pennsylvania State University, discusses why we should study Astronomy. This is our first video blog post - let us know what you think about the video and this format in the comments!

Showing posts with label Jonathan Trump. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Jonathan Trump. Show all posts

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

Tuesday, February 5, 2013

AAS and the Job Hunt

|

| A wordle made up of the 250 most common words from the AAS abstract book. Image credit: Jim Davenport |

For many astronomers, the path to finding a job includes a stop at the annual American Astronomical Society (AAS) meeting. The conference provides several dimensions to help recent Ph.D. graduates and postdocs find a job: interviews, workshops, networking, and simply presenting your work in front of a wider audience. As a junior postdoc and recent Ph.D. graduate myself, I fall squarely into the AAS job-hunter category.

With so many astronomers (over 3000 this year) traveling to the AAS, it ends up being a convenient place for many employers to hold interviews for prospective job candidates. This includes both tenure-track faculty jobs and postdoctoral research positions. Like in any career, an interview gives employers a chance to get to know their candidates face to face. Personally, I find these interviews to be exciting opportunities: it gives you a chance to brainstorm new research ideas with experienced senior astronomers.

The AAS also offers several workshops for resume-building, grant writing, and interview tips. I haven't actually attended any of these workshops, but I do have a lot of experience with the networking side of the AAS. Sometimes this means finally meeting a colleague in person when you've only swapped emails before, and sometimes it means trying to spearhead a new observing campaign or data analysis plan. Networking also provides opportunities to meet astronomers who might be offering attractive postdoc jobs in the near future. The AAS is also one of the few meetings where industry and science policy professionals attend: if you are an astronomer seeking a non-academic job, the conference provides a rare outlet to network with potential employers.

With over 3000 astronomers, the AAS is simply the largest astronomy conference of the year. This means your talk or poster presentation will have a much larger audience than at smaller conferences. For this reason, the AAS is one of the few meetings where astronomers are unusually well-dressed. I suppose you never know which future employers might be at your talk, and it doesn't hurt to show that you are serious about your work.

The search for a job as a professional astronomer is not easy: there are many more qualified applicants than there are jobs (both temporary postdoc and permanent faculty). But the AAS provides a rare opportunity for face-to-face time with potential employers. For me, this is the biggest service the meeting provides, and it makes it an important meeting for recent Ph.D. graduates and young postdocs.

Friday, July 13, 2012

Growing Black Holes in Teenage Galaxies

About a decade ago, astronomers began to realize that nearly all massive nearby galaxies have supermassive black holes in their centers. Strangely, the mass of this enormous black hole is well-correlated with the total mass of the collection of stars in the inner part of the galaxy: this inner galaxy structure, called the galaxy bulge, is always about 500 times as massive as the supermassive black hole. That is, a galaxy bulge with a mass equal to a billion Suns will have a supermassive black hole with a mass of two million times the mass of the sun.

Both galaxy bulges and supermassive black holes grow with time. Galaxy bulges build up mass by forming stars and merging with other galaxies, and black holes grow in "active galactic nuclei (AGN)" phases by accreting gas, dust, and stars within their event horizons. In order to maintain the observed correlation between their masses, galaxies and their black holes must grow together, with the galaxy bulge always growing around 500 times faster than the black hole. Somehow the black hole and the galaxy "know" about one another as they both grow.

This leads to an interesting "chicken or egg" question: which comes first, the galaxy or the black hole? Do tiny young galaxies in the distant past already have growing black holes? Or is the close link between galaxies and their black holes only a recent development?

|

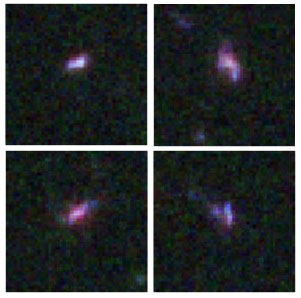

Four examples of adolescent, low-mass galaxies in

CANDELS which host growing AGNs. Image credit:

A. Koekemoer, Space Telescope Science Institute |

To find the black holes, we had to combine the deep CANDELS imaging with the unique HST infrared grism spectroscopy in the same field. The HST grism is unique because it provides both spectral information and spatial data. So the grism not only disperses the light from a galaxy into a spectral rainbow, but it also allows us to compare an inner galaxy spectrum with the outer spectrum of the same galaxy. This is particularly useful for finding AGNs, which tend to strongly affect the interior of a galaxy without changing the outer region too much.

Accretion onto a black hole produces much more UV and X-ray emission than typical galaxy starlight. High-energy photons are very efficient at ionizing atoms, producing a tell-tale emission line signature in a spectrum. Because AGNs live in the centers of galaxies, they cause a markedly different ionization signature in a galaxy's interior compared to its outer region -- and the CANDELS grism data revealed this very feature in several distant and low-mass galaxies.

Accretion onto a black hole produces much more UV and X-ray emission than typical galaxy starlight. High-energy photons are very efficient at ionizing atoms, producing a tell-tale emission line signature in a spectrum. Because AGNs live in the centers of galaxies, they cause a markedly different ionization signature in a galaxy's interior compared to its outer region -- and the CANDELS grism data revealed this very feature in several distant and low-mass galaxies.

Four examples of these teenage galaxies with growing black holes are shown in the graphic above. As you can see, they look like barely-detected smudgy little disks. They are particularly interesting because they don't seem to have the bulge structure seen in the centers of local galaxies with growing AGNs. It seems that we've determined that the black hole "egg" actually comes before the galaxy bulge "chicken!" And it's a testament to the tremendously deep CANDELS imaging and spectroscopy that we can learn about growing black holes in such faint teenage galaxies.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)